Evolving Code at Test Time — Building a Mini AlphaEvolve on My Laptop

Most AI systems work like a vending machine: you put in a prompt, and you get a single, immediate answer. But as I explored in a previous post on story generation, some of the most exciting progress in AI is happening when we let models “think longer” about a problem. Instead of one forward pass, they use their inference-time compute to search, iterate, and refine their outputs.

DeepMind’s original AlphaEvolve paper is one of the most ambitious examples of this. It uses an evolutionary approach to discover new, more efficient algorithms from scratch, and its power was recently showcased in a follow-up study on mathematical discovery (Georgiev et al., 2025). After reading the original paper, I couldn’t resist trying to build a tiny, laptop-scale replica 🤔 – a project I’m calling Mini Evolve.

My goal wasn’t to create a production-ready system, but to get a hands-on feel for the core idea: what happens when you let an LLM write, test, and evolve code, guided only by a single performance score? This post is the story of that experiment, what I learned, and why this pattern of test-time adaptation feels so powerful.

An Experiment in Code Evolution

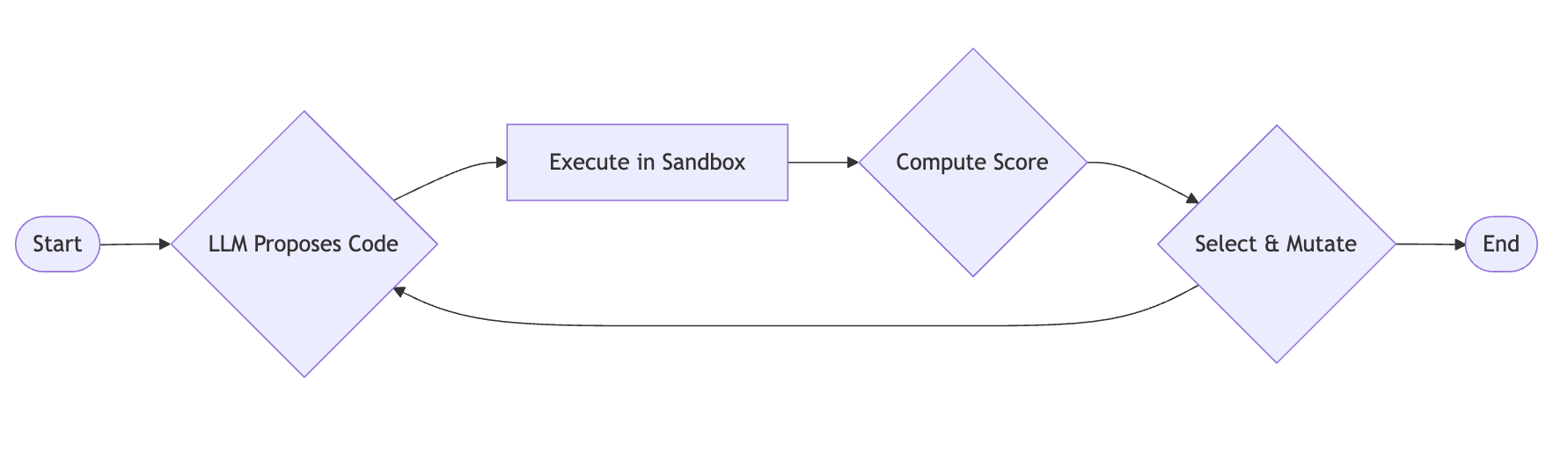

The core idea is a simple but powerful feedback loop: an LLM proposes a solution as code, the code is executed, its performance is scored, and that score guides the next generation of solutions.

To bring this loop to life, I aimed for a setup that was more robust than a single script but still manageable on my laptop. I landed on a simple, container-based distributed system using an orchestrator-worker pattern.

An orchestrator process manages the main evolutionary loop, sending out jobs to one or more workers–this allows the system to scale horizontally. These workers are responsible for prompting the LLM to generate new code. I used Redis as a lightweight job queue and to track the results of each experiment.

Another critical piece, however, was safety. When a worker receives a new program from the LLM, it doesn’t run it directly. Instead, it spins up a new, heavily sandboxed job container just for that execution. These containers have no internet or host access and run with strict time and resource limits, which was my way of letting the LLM explore creatively without risking it going rogue 😅.

Finally, the entire process is guided by a user-defined scoring function that takes the output of the code and returns a single number—higher is better. This is the only “guidance” the system gets.

The process itself is a miniature evolutionary search, running as a continuous flow of jobs. The orchestrator seeds the Redis queue with initial tasks. Workers pick them up, prompt the LLM to generate a new code candidate, and push it into a sandboxed container for testing.

As scores for each candidate come back, the orchestrator makes its selection for the next generation. It doesn’t just pick the top performers; to maintain genetic diversity and avoid getting stuck in a local optimum, it also includes a few suboptimal but diverse candidates with a small probability. It then creates a new batch of “evolve” tasks based on these selected programs, and the system hums along, constantly refining its population of solutions.

Let It Build an ML Pipeline

With the system in place, I needed a test case. I gave it the 20 Newsgroups dataset from scikit-learn and a simple scoring function that returned a weighted sum of the model’s classification accuracy (80%) and an execution time penalty (20%). Crucially, I didn’t tell the LLM anything about what models to use, feature engineering, or what a typical ML pipeline looks like. The only thing the LLM could see and modify was the solve() function, which contained the initial, suboptimal pipeline.

Click to see the full seed script and scoring function

def scoring_function(result):

"""

Score based on text classifier accuracy and performance.

- Trains on a split of scikit-learn's 20 Newsgroups dataset using the `result` trainer.

- Tests on a held-out set.

- Combines correctness (accuracy) and speed (train + predict time).

"""

import time

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_20newsgroups

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Load data (remove headers/footers/quotes to reduce noise)

data = fetch_20newsgroups(subset="test", remove=("headers", "footers", "quotes"))

X, y = data.data, data.target

# Fixed split for repeatability

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42, stratify=y

)

# Train the model using the provided training function

try:

start_train = time.time()

model = result(X_train, y_train) # must return a fitted estimator with .predict

train_time = time.time() - start_train

except Exception:

return 0.0 # training failed

# Predict on the test set

try:

start_pred = time.time()

y_pred = model.predict(X_test)

pred_time = time.time() - start_pred

except Exception:

return 0.0 # prediction failed

# Correctness (accuracy)

accuracy = float((y_pred == y_test).mean()) # 0..1

# Performance scoring: encourage quick training and inference

max_train_time = 10.0 # seconds

max_pred_time = 3.0 # seconds

def time_to_score(elapsed, cap):

if elapsed <= cap:

return 1.0

# decay scale: every extra cap reduces score by 1.0

return max(0.0, 1.0 - (elapsed - cap) / cap)

training_score = time_to_score(train_time, max_train_time)

prediction_score = time_to_score(pred_time, max_pred_time)

performance_score = 0.5 * training_score + 0.5 * prediction_score

# Final weighted score: accuracy (80%) + performance (20%)

final_score = 0.8 * accuracy + 0.2 * performance_score

return final_score

def solve():

"""

Return a function that trains and returns a fitted scikit-learn text classifier.

"""

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

def train_model(X, y):

model = make_pipeline(

CountVectorizer(

lowercase=True,

),

LogisticRegression(max_iter=500, solver="liblinear")

)

model.fit(X, y)

return model

return train_model

result = solve()

score = scoring_function(result)

print(f"SCORE: {score:.4f}")

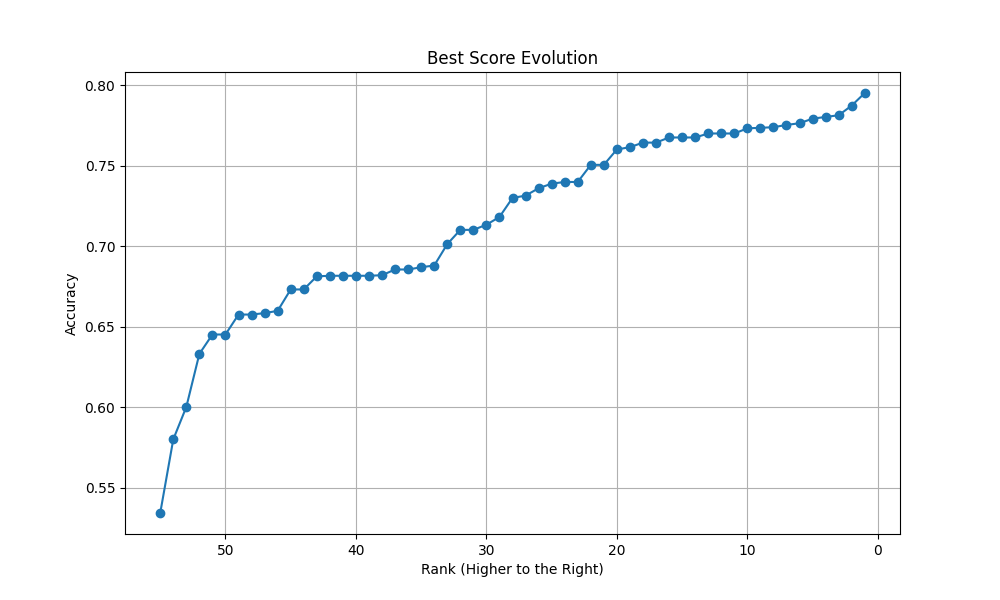

Over several generations, something fascinating happened ✨. The system started discovering better approaches on its own, first by more obvious changes, but later adding more nuanced elements. It swapped CountVectorizer for TfidfVectorizer, added stop_words, and even found useful parameters like sublinear_tf. It eventually settled on a much more refined pipeline:

model = make_pipeline(

TfidfVectorizer(

lowercase=True,

stop_words='english',

norm='l2',

smooth_idf=True,

use_idf=True,

sublinear_tf=True

),

SelectKBest(chi2, k=8000),

SGDClassifier(max_iter=1000, tol=0.001)

)

Why This Matters (Even at a Small Scale)

This little experiment reinforced just how powerful the “search-at-inference-time” paradigm is. It’s not about finding the world’s best classifier, it’s about what this pattern represents.

- Adaptation is the Killer App: The model adapted its solution to the specific problem while solving it. It didn’t rely on pre-trained knowledge alone; it used feedback to discover what actually worked.

- Beyond Bigger Models: This approach offers a path to better results that isn’t just “train a bigger model.” It’s about using compute more intelligently at inference time.

- Grounded in Reality: By executing code and getting real feedback, the LLM is forced to generate solutions that work in practice, not just ones that look plausible as text. The score doesn’t lie 😉.

Ultimately, Mini Evolve is a glimpse into a design space where we don’t just prompt models for answers. Instead, we give them goals and let them build, test, and discover their own solutions.

What’s Next?

While this was a side project I’ve been building in my free time, it has definitely sparked more questions than answers (as usual 😅). I’m not planning to open-source the code just yet, as many parts still need to be made more configurable. For instance, the prompts that guide the LLM’s mutations are currently hard-coded Python strings, and generalizing them is a project in itself! 😂

If there’s interest, I might write a follow-up post diving into some of these internal mechanics.

But what I’m most curious about is what you would do with a system like this. I’d love to hear from readers, especially those with domain expertise in fields outside of machine learning. What’s a tricky optimization problem in your area—be it in logistics, biology, or finance—that you think would be a fun challenge for an evolutionary code-writer? Let me know your ideas! If you want to connect, you can find links to my GitHub and LinkedIn profiles on my home page.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: